More died from flu than from bullets that year… That was the

sad truth in America in 1918. World War

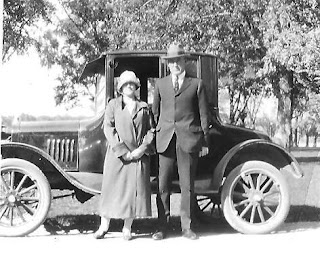

I was raging, but so was an influenza epidemic like the world had never seen. Theodore Peterson—my great uncle Ted—was an

engineering student at the University of Nebraska when duty called. He never made it to Europe.

Although this photograph taken at his funeral is

heart-wrenching to me, so too are the words of his sister Sara. She wrote this letter to Sture, her

sweetheart, on October 16, 1918—just days after Ted died of influenza at an

army camp in Fort Grant, Illinois. Their

mother had lost her beloved husband Charles in 1917, and then her beloved son

Ted just a year later.

“Mother is keeping up splendid, but the first few days are

not near as hard as it is afterwards. We

girls have been talking of sending her out to California for the winter at

least. Carl (my brother) is in San Francisco , you know,

and they have been wanting her to come for so long. This winter will be so long and lonesome for

her here. If she gets out there she may

be able to not think so much. But I

haven’t heard her complain—not once. She

is as brave a soldier as any.”

Sara wrote this a week later:

“Though I didn’t go to see the boys off today, I’ve been

thinking of the day Ted went. I don’t

believe Ted ever felt happier in all his life than the day he went. At last he was going to realize what had been

his one wish and ambition ever since this war started. And I can’t help but think, why oh why

did he have to die, before he had a chance to accomplish some part of

what he was so anxious to do. It’s hard

for us mortals to see the why of these things.

But it must be all to the best, for these things do not just happen,

they are brought about by the Divine will.

It’s so hard to believe that is it the best, when we can’t see the why

and wherefore. But after all, surely I

can be as brave as Mother, for surely to lose a son must be harder than to lose

a brother. And she says that after all

and in spite of all, she wouldn’t had Ted done any other way than he did. She is glad and proud that he wanted to go.

Sture, I said once about a year ago, that I would rather my

brother would go, even if it meant that he never came back, than to have him

take the stand of some of our other young men I know. These words of mine have come to my mind so

often these days, and while perhaps at the time I spoke them, I didn’t weigh

them as I have since, I know deep in the bottom of my heart I meant them, and

now I have come to the test. And while

it almost breaks my heart, dear, I can still say with all sincerity, that I am

glad he took the course he did. I would

be unworthy of him and his sacrifice if I felt otherwise.”

For every soldier who died, whether on the battlefield or

from the ravages of the flu, there were those who remained to mourn.